[brushes away the dust and cobwebs]

Well now…it’s been a while, hasn’t it?

After my discarding of active participation in social media in early 2016 (due to…multitudinous reasons not worth going into here), the continuation of this blog without a means to properly promote its content seemed largely futile. This did unfortunately cut the largest swathe of recreational writing possibilities out of my life, and left a lot unsaid. The dedication to evaluate every remaining episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation? A promised and well-deserved evisceration of Clannad: After Story? In all likelihood, these projects are lost now, like interstellar dust drifting further and further into the void between starlit systems. And that’s without getting into how retroactively charged a title like “Paragraph Plague” suddenly feels at the time of writing. It was always going to take something very special to drive me to post here again at all, considering damn-near nobody was ever going to read it.

But something special did come along. Something that unexpectedly and subtly planted a seed of inspiration in me. Something that deeply challenged my existing outlook in a way so few things can. Something that compelled me, at long last, to spill forth my innermost thoughts unrestrained, lest the half-imagined fevered dreamscapes it inspired in my mind drain my sanity by being locked within.

I am, of course, referring to niche horror-themed Playstation 2 software. Obviously.

It wouldn’t be easy to determine from the previous contents of this particular blog, but survival-horror video games circa roughly 1996 to 2004 — typified by fixed overhead camera angles, limited resource management, progression gating by way of hidden key items, and various degrees of scares — are something of a “pet genre” of mine, something I am deeply fascinated by and find myself constantly returning to for study. Clock Tower 3 (for all its eccentricities, which will be discussed in due time) fits snugly into this category, but not without a handful of stand-out on-paper attributes to illuminate it among its many peers. The “Clock Tower” name itself is among them, bonding it to a franchise that predates the genre’s biggest “boom” period and was instrumentally influential upon it. The name of its co-producer and developer, Capcom, is another, in no small part due to their codification and popularization of this very style of game through the Resident Evil series.

But most notable of all would be the name of its co-director, Kinji Fukasaku. Purely within the realm of interactive software, the name would register little; Clock Tower 3 remains his only video game credit. But the man has a storied feature-film career dating all the way back to 1961, with more than 60 directing credits to his name spanning a colossal variety of genres and styles. Viewers not familiar with the broader catalog of his work would still almost certainly recognize the name of at least one of his creations: Battle Royale, the novel adaptation that released in 2000 to much controversy, acclaim and lasting legacy alike. Tragically succumbing to prostate cancer in early 2003, both his most internationally-famous film and his sole contribution to video gaming stand as among his final works of art.

None of these factors, however, were enough to bring Clock Tower 3 to prominence. Upon its release into the wild, it was savaged by tepid review scores and pitiful sales, the latter of which achieving barely over a quarter of Capcom’s projections. What’s more, the game never seemed to achieve the posthumous cult following so many such sales failures hope to attain. I speak largely from an anecdotal standpoint, mind you, but even as someone who occupies the sorts of circles that would bound in joy at the mention of, say, Siren or even The Suffering, Clock Tower 3 is a name I haven’t seen invoked in conversation since its release. I only even remembered its existence at all from vague recollections of its lackluster advertising and middling review scores in video game magazines of the day (relics of a long-gone time, I recognize). It doubtlessly has its fans (including fan-fiction authors, apparently), but I can’t help but perceive that its lasting footprint on the golden age of survival-horror has been washed clean away by the waters of time.

…which, having now played the game myself, I consider to be an almost appalling shame. Despite its often-baffling creative decisions (or perhaps, indeed, because of them), it is a singularly special, almost hypnotically fascinating work that has been malnourished of the attention and conversation it so visibly warrants.

Clock Tower 3 makes a strong impression from the moment you select “new game”, when Fukasaku’s presence on the staff is first made apparent. Simply put, the game’s numerous cutscenes are extraordinary, owing not just to the directorial expertise applied, but also to the downright lavish motion-captured animations employed. Both in and out of pre-renders, the cast of humans and monsters alike move with a vibrantly expressive energy that captivates without becoming overzealously distracting (most of the time). This artistry then bleeds outside of the cutscenes and into the environments, each carefully crafted to ring darkly true of exaggerated pseudo-Gothic London streets, graveyards, manors and castles (and the occasional Egyptian tomb, because nothing says “Britain” like the lasting remnants of colonial antiquities theft). Given the sheer amount of optical character on display throughout the game’s spiraling narrative and many changes in scenery, I’d go so far as to say that Clock Tower 3 is among the upper echelon of visual experiences released for the Playstation 2. It isn’t exactly Silent Hill 3 or Shadow of the Colossus in that department, but there are select times when I feel it comes within striking distance of such titans.

Where things get truly interesting, however, is in how the game chooses to channel this boundless energy it has cultivated. As becomes quickly apparent, it chooses to do so in a number of…let’s say, seemingly incongruous ways.

As a broad outline, the plot of Clock Tower 3 is almost fiendishly dour. Chiefly, it concerns Alyssa Hamilton — a British boarding-school student on the cusp of her fifteenth birthday — discovering all too rapidly that she is descended from a long bloodline of matriarchal warriors destined to do battle with evil spirits, and that her very own grandfather is seeking to perform an immortality ritual that requires devouring her heart. The aforementioned evil spirits are an omnipresence throughout the game; each distinct “chapter” of the story is patrolled by a unique “Subordinate”, a serial murderer whose visceral and appalling crimes you frequently witness first-hand, perversely illustrated with the director’s typical attention to detail. Even the victims of these devils are not yet free of their torment, tethered as ghosts to the site of their defilement until Alyssa can find a way to soothe their rage. As the vile schemes of the villains are gradually revealed and the souls of the damned swarm around you in greater and greater numbers, the “horror” of this “survival-horror” game would appear almost overbearing…

…were it not for a few key details I have omitted.

For starters, the Subordinates, no matter how many lives they have cruelly taken, are portrayed by the game not as grimly realistic but as downright silly, complete with Captain-Planet-villain-esque vocal performances. And while Alyssa may be theoretically unarmed and helpless to put a permanent stop to their pursuit for most of the game, she is always equipped with a handy vial of sacred holy water that she can splash in their faces, comically stopping the hulking madmen in their tracks as simple water burns them like sulfuric acid. Better still, the game’s environments are frequently littered with context-sensitive action points that allow Alyssa to temporarily get the upper hand on her foes in stupendously over-the-top and frankly badass ways. In one such instance, Alyssa incapacitates a gargantuan, sledgehammer-wielding maniac with a single precise toss of a violin case. In another, she bursts out from behind an outhouse door to catch her pursuer unawares, causing him to become flattened, paralyzed and slowly collapse to the ground in a manner almost exactly reminiscent to that of a Looney Tunes short. The game isn’t just “not scary” in these scattered interactions: it’s laugh-out-loud funny.

Each chapter oscillates between moments of helplessness and moments of slapstick in this fashion before finally climaxing in a boss fight (the health bars of which are determined by the length of the Subordinate’s prison sentence, naturally). And it is here that the game most resembles not a survival-horror title nor a Saturday morning cartoon, but rather yet another “pet genre” of mine: the magical girl anime. After a luxurious animated sequence more reminiscent of Junichi Sato than George A. Romero, Alyssa’s vial of holy water transforms into a magical longbow, that she may bind the Subordinate in place and purge them of their evil in with an arcane, ponderously-long orbital strike finishing attack. With victory hers, she is able to reunite a particular lost soul with their loved ones in the afterlife, in an attempted-heartstring-tugging sequence of fond goodbyes and tinkling piano keys. Clock Tower 3 seems to so closely ape the conventions of the magical girl genre in these moments — from the visual coding to the heartwarming epilogues to even the overarching episodic “monster/victim-of-the-week” story structure itself — that I wouldn’t be surprised to learn if Fukasaku had nestled his copy of the Battle Royale novel alphabetically on his bookshelf snugly between volumes of Akazukin Chacha and Cardcaptor Sakura.

That these dissonant intonations and styles should even occupy the same disc is one thing. But Clock Tower 3 is already not a particularly lengthy experience (a mere handful of hours, all told), and these massively divergent tones are stacked atop one another as densely as canned sardines, such that whiplash between them is not a matter of “if”, but “when” and “how often”. You’ll watch a scene of a kindly son gifting a hand-made shawl to his ailing mother…just before both of them are quickly dissolved in a barrel full of acid by a gas-mask-wearing psychopath. You’ll witness a flashback of Alyssa as a baby being gifted a priceless family heirloom and laughing for the first time…quickly followed by her father being pushed off a guardrail and having his skull comfortably cushioned by an upturned axe. You’ll recoil in horror at Alyssa’s childhood friend (who bears a striking resemblance to actor Rupert Grint) being graphically cleaved in twain by a bladed pendulum…only for the villains to reveal that it was a suspiciously-well-crafted dummy, just to mess with the player’s head.

Did I mention that all of this occurs as Alyssa is travelling through time? That seems important to make clear.

I will take a moment here to state outright what some may already be thinking at this point: none of this should work. At all. Indeed, if its aforementioned launch reception is anything to go off of, it plainly did not work for a good many people.

It is tempting, perhaps, to levy its commercial failings at its gameplay and the marketability thereof moreso than its storytelling. I was there in the thick of it, and by late 2002 a mentality was beginning to circulate within gaming publications (if not the gaming public as a whole) that the mechanical foundations of the contemporary survival-horror game were archaic and old-hat, a rod Capcom themselves may have assisted in making for their own back through their perpetual flood of Resident Evil titles oversaturating the market. That same weariness of the genre’s roots would later result in the completed development of Resident Evil 4 a scant two years later, which rejected the previous emphases on directed camera angles and enemy evasion with an over-the-shoulder vantage point and precise tactile combat. The industry-wide paradigm shift that title caused leaves Clock Tower 3 as among the last of its kind, and it clearly did not receive the sort of fanfare being the last of your kind is “supposed” to net you.

Still, I wouldn’t attribute the gameplay as the primary alienating factor. Games like Silent Hill 2 and Fatal Frame II: Crimson Butterfly, released within roughly the same time frame with many overlaps in mechanical design, are hailed to this day as classics, and rightly so. The difference here, I feel, is that of constancy. Silent Hill 2 and Fatal Frame II are beloved in no small part because of the consistency of their vision in the painting of pointedly-specific emotional landscapes (those of chronic melancholia and oppressive fear, respectively). By contrast, when you have a game ping-ponging at such violent speeds between horror, ham, and heart, it becomes far easier to draw the conclusion that the creative minds involved simply did not know what they were doing.

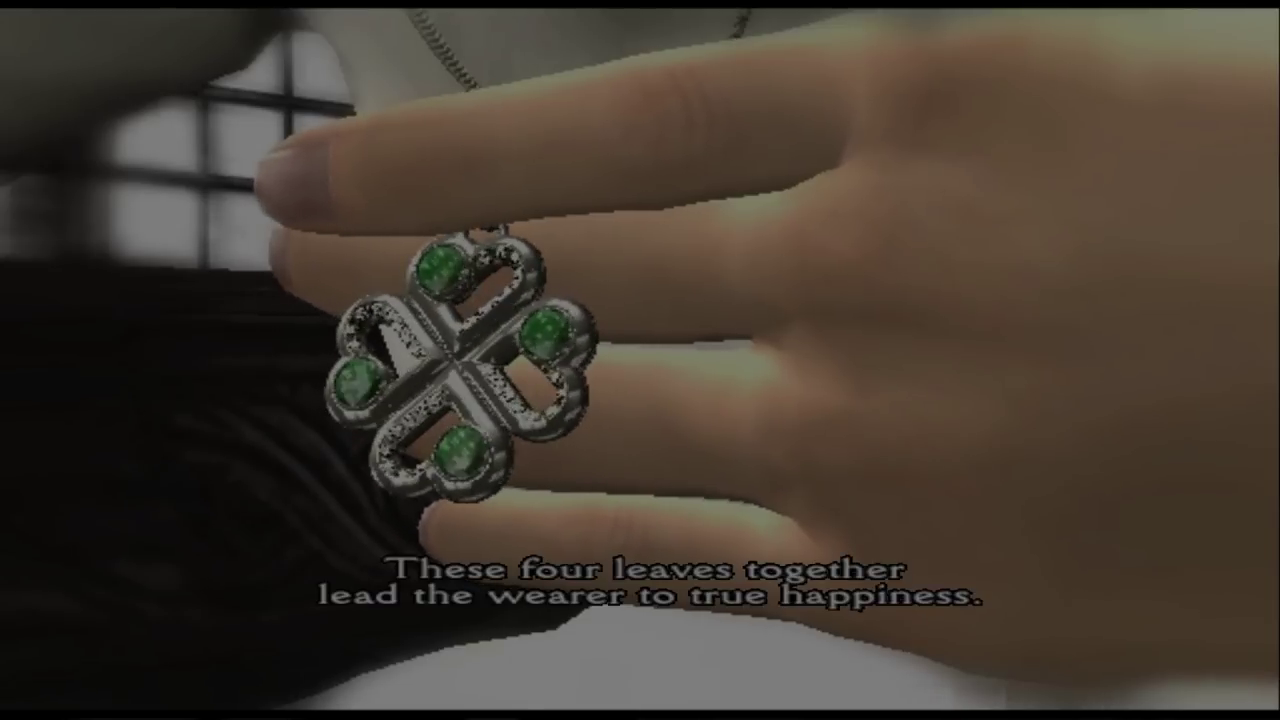

But make no mistake: I think they very much did. Admittedly, it took me some time to parse exactly why I felt that way, why I regarded the creator’s strange decision-making with such reverence and respect rather than mere laughter (though laughter was prevalent still). What I ultimately landed upon was not a mere abstract argument, but an artifact present in the story itself: the Clover Necklace.

The Clover Necklace, passed down the Hamilton family line for generations, is made of four conjoined pieces of jewelry: the Clover of Love, Clover of Courage, Clover of Hope, and Clover of Strength. Hokey in their naming conventions? Absolutely. But however hokey they are as ideas, I was forced to reach the eventual conclusion that love, courage, hope and strength are fundamentally what Clock Tower 3 is actually about. Wash off the blood and grime from the proceedings, and this is a fairly simple story of a young pubescent girl being thrust into an unenviable position, not giving up and maturing as a result (again, the parallels to the traditional values of the archetype magical girl story are plain as day here, though perhaps with less of the attendant baggage). “Strength”, the final clover recovered of the four-piece necklace, can be said to be the product of said maturation. But the other three are the crucible in which that strength is forged. Alyssa triumphs over evil in the end not because she is physically stronger than the agents of evil, but because of the weapon she wields that so few others in the story do: social empathy.

Remember, this is a game that routinely punctuates its largest story beats with resolving the conflicts of minor characters who died before they could become emotionally fulfilled. It is crawling with dangerous spirits that Alyssa can absolve by providing them with an item of worth from their corporeal life. In sharp contrast, the villains are almost literally calculated in threat by their psychopathy, their deficiency in ability to care at all about these people in pain (again, I stress: prison-sentence-dependent health bars). To say that this dichotomy is rare to the survival-horror genre would be an understatement, but it is nonetheless a clearly and rigidly defined one within the game’s text, and in-so-doing becomes the axis upon which the massive tonal shifts successfully pivot. Clock Tower 3’s silliest moments instead become triumphant with the understanding that the game desires to inspire just as much (if not moreso) as to terrify. When Alyssa overcomes her stalker by, say, tricking them into taking a headfirst dive into a burning oven, we do certainly laugh, because the image is absurd. But it is only part-and-parcel to the cheering we are also doing for her love, courage, hope and strength in these moments. The clover shows the way.

If we hold the above to be true, then the decision to set this particular emotional tenor against the backdrop of a survival-horror game with such a bleak central conflict actually becomes very telling. The message it seems to suggest, I feel, is that even within the grimmest of realities — where the most vile individuals live the longest and richest lives, the innocent die without warning nor rationale, and all of our deepest desires seem destined to go unfulfilled — good still exists. Every small mercy performed, every injustice set right, every relationship forged and maintained…each may be a trivially small weave in the grand fabric of the universe overall, but Clock Tower 3 would not have us forget that every single one nonetheless has unfathomable value. And to do so, it utilizes tonal dissonance not as a bug, but as a feature.

The technique of interweaving levity with dread to produce a more layered emotional gradient is not, in itself, terribly new, what with the “comedy horror” being its own acknowledged genre and all. In the world of film especially, I would point towards Nobuhiko Obayashi’s House, Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead II, and Peter Jackson’s Braindead as but a few beloved works of art well-known for striding the blurry lines between laughing and screaming. To see a video game do exactly that, representing different expected reactions with different states of interactive play, has a certain comparative novelty. But more importantly, I would argue that Clock Tower 3’s goals in walking along this line are not just more thematically-oriented in nature, but possess an explicitly more optimistic bent than its cinematic peers. There is no tongue-in-cheek irony present here, no sarcasm undermining the game’s moments of genuine joy. The dissonance, instead, is as earnest as it is entertaining, and is the key to making the game’s sanguine lesson sing: that light shines the brightest when all else is shrouded in darkness.

Call me crazy, but something about all of that resonates with me quite strongly in the year 2020, of all years. On a more personal note, as someone with a recently-increasing clarity that my more rough-edged surface-level personality traits — my snark, my cynicism, my death metal album collection — also double as a social mask for a pent-up ball of manic sentiment and affection and hope…well, you could say I sympathize pretty damn hard with the general concepts of contrast and tonal dissonance right about now. Inject all of that contrast and tonal dissonance directly into my veins, please. We are now as one.

Perhaps this is all a bit too much weight to lay on the shoulders of a franchise sequel from 18 years ago that features character names such as “Sledgehammer” or “Scissorman”. You could certainly make that argument, and even in light of everything just written I doubt I would even dispute it. But what I am long-windedly getting at is this: however dismally Clock Tower 3 failed in its own time, I have personally found a non-trivial amount of cheer and value in playing it in the modern day. Whether by ambiguous intent or delightful accident, the creatives at Capcom and Sunsoft created something that is as unique as it is surprising as it is weirdly poignant. I won’t soon forget it, and I doubt anyone else I have thus far shared the experience with will either.

So here’s to you, Clock Tower 3: you flawed, weird, erratic, beautiful inspiration to us all. And here’s to writing more sometime soon!

Probably.

Possibly.

Maybe after the dust and cobwebs build back up again.

I was clearing out my bookmarks when I came across PP Plague. I remember following along your Sailor moon rewatch back in the day, and I thought you were lost to the great churn of the internet. it’s nice to see that you’re still hangin’ around. For the record, I’m always down for an evisceration of Clannad AS.

LikeLike